The final few months of David J. Zanghi Sr.’s life were extremely difficult, to say the least.

In November 2019, the lifelong Batavian became an unsuspecting victim of a domestic dispute that turned into a 20-hour standoff at 209 Liberty St. Zanghi resided in the downstairs apartment; the incident involved the tenant who lived upstairs.

The aftermath of that event resulted in Zanghi having to find another place to live due to the damage caused by police officers during their attempt to talk the perpetrator -- who was armed with a knife and BB gun -- into surrendering.

It was, according to his sister and advocate, Mary Ellen Wilber, too much for the physically and emotionally impaired Air Force veteran to deal with and sent him into a downward spiral that ended with his death on March 27.

Zanghi, affectionately known as the “Mayor of the Southside” due to his outgoing and caring demeanor, succumbed at the age of 67 after going into cardiac arrest at Strong Memorial Hospital of the University of Rochester.

The cause of death?

“He died of COVID-19,” said Wilber, speaking by telephone from her New Jersey home on Thursday. “The Health Department has said there is one Genesee County resident who has died (from the coronavirus) -- a male over the age of 65. That person is my brother, David.”

The Batavian was unable to confirm with authorities that Zanghi died of COVID-19 but, nonetheless, Wilber’s story is quite compelling.

'Thing with the City ... that destroyed him'

She said her brother suffered from end-stage kidney failure (he was on dialysis), diabetes and heart disease, and also was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

He had managed to keep things together in his adult years, she said, by regularly connecting with family, friends and neighbors. Everything changed, however, following the standoff.

“The thing that happened with the City, I’ll be honest with you, that destroyed him,” said Wilber, who contends that law enforcement used the Liberty Street incident as a tactical exercise.

“He lost faith in his community. David was such an outgoing, loving and caring person. Everyone on the Southside as we grew up knew him as Davey Joe. As an adult, he was David.”

Wilber said her brother became despondent over what he perceived as the Batavia police’s lack of concern for his situation – the destruction caused by hundreds of tear gas canisters – and that despair turned into paranoia.

“So, when you have a person who never caused any problem in the City of Batavia, who had always been good in the City of Batavia, was a good neighbor to the neighbors next door, to the neighbors on Liberty Street, was cordial and had always been cordial to the police – and you can ask the police officers if my brother had always been cordial to them -- … and you discounted all of those things and treated him horribly,” she said.

“It undermined his mental capacity and he was afraid of what they would do to him next because no one ever cared about what they did to him.”

Zanghi eventually was relocated by his landlord to a home on Grandview Terrace (after plans to go to an apartment on Summit Street didn’t work out), Wilber said. He was lonely and depressed, she said, and he fell down on more than one occasion -- the last time fracturing his shoulder in February.

“The shoulder got infected, David got sick and became disoriented, developing a fever of 101,” Wilber said. “So, we took him to the U of R (Strong) and the infection went through his whole body. He had bacterial pneumonia.”

Family asked doctors to check for coronavirus

During his 10-day stay at Strong, Wilber said she and her sister, Michelle Gaylord, “repeatedly asked (doctors) to make sure you check Zanghi for COVID-19."

“They said no COVID, everything’s fine. Then they did two major operations on his shoulder (on March 19 and 21), and they day before he died the social worker and I were planning for his discharge. He was medically stable,” Wilber said, adding that the family was looking at putting him in the NYS Veterans Home on the VA Medical Center grounds in Batavia.

Wilber said her brother was “doing great but we were kind of curious because he was so tired.”

“When you have COVID-19, you’re exhausted because the COVID is taking over your body," said Wilber, whose has worked for the Center for Disease Control on special projects and has taught about HIV for 35 years.

“So, when he died on that Friday, the doctor said your brother’s pulse stopped. His heart just stopped. Well, a side effect of COVID-19 is sudden cardiac arrest.”

While she holds no ill will against the doctors and nurses at Strong, Wilber said she was livid when she found out that they did not test her brother for COVID-19 while he was alive, but did test him right after he died.

'My brother got COVID-19 while he was up there'

“He got infected there because all of us were previously tested and none of us who were with David have got the virus,” she said. “What makes this wild is that my brother got COVID-19 while he was up there. He died from it. They told us that he tested positive and what makes us crazy is that he got infected by somebody up there and, in turn, he exposed everybody that he came in contact with.”

Wilber said her brother was in the emergency room for two and a half days – “he probably got it down there,” she presumes – and then he went in for X-ray, CAT scan, ultrasound and blood work.

“Then he was on the sixth floor for almost eight days … all the nurses, all the doctors, the surgeons, the specialists, all the lab people – all of those people were exposed to COVID-19,” she said. “I have lost so many nights' sleep praying for those healthcare workers. Do you know how ridiculous U of R is because they never tested him? They would have found that before he died. They could have put him in isolation. I called the governor’s office, got a special advisor –and messaged him, I want you to know this.”

An administrative assistant returning phone calls for Strong Memorial Hospital’s public relations department verified this morning that Zanghi was a patient there and did pass away there on March 27. She said HIPAA laws and patient confidentiality restrictions prevented her from providing other information.

Wilber: Family notified health department

Wilber said her sister notified the Genesee County Health Department of Zanghi’s death by COVID-19.

“And then they have a news conference and he (Director Paul Pettit) is breaking the news – saying that the health department notified the family,” she said. “Kiss my butt. My sister called them and told them my brother died of it.”

Wilber, who grew up on Wood Street in Batavia, said she is in the process of moving to Attica (Wyoming County) because she said she will never live in Genesee County again after the way the police treated her brother.

She said she wants to thank City Manager Martin Moore and Assistant City Manager Rachael Tabelski and the residents of Batavia for their kindness and to Rosanne DeMare of Genesee Justice who “went over and above.”

David Zanghi also leaves behind two sons, David Jr. of East Pembroke and Alex of Texas; sister, Rosanne Wray of Batavia; brother, Philip of Las Vegas, and their families; four grandchildren and numerous nieces and nephews.

Wilber said a memorial service is planned for this spring or summer at Ascension Parish in Batavia, and that her brother will be buried at the Western New York National Cemetery in Pembroke.

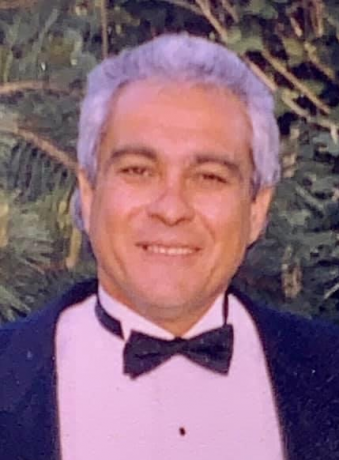

Photo: David Zanghi Sr. on his front porch of his former residence at 209 Liberty St. Taken by Howard Owens following the 20-hour standoff in November 2019.