The GOP Plan: Border Adjustment Tax

This is part six of an eight-part series on trade and how changes in policy might affect the local economy.

Editorial cartoon from 1912 illustrating the dilemma of tariffs: protect profits for producers, harm consumers.

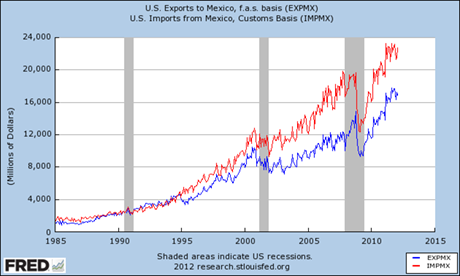

President Donald J. Trump, as he did as candidate Trump, talks trade deals and the need for creating a series of bilateral agreements. He also threatens tariffs against countries he thinks are taking advantage of the United States such as Mexico and China.

But congressional Republicans have their own plan, though it's not one it's at all clear Trump supports.

The proposal, called a Border Adjustment Tax (BAT), is part of a broader push by the GOP to reform the tax code and lower corporate taxes.

The BAT changes how companies pay taxes on their profits. Effectively, imports would be taxed and any profits from exports would be tax free.

The goal is to encourage more U.S. manufacturing and protect domestic companies from lower-priced imports.

Rep. Chris Collins supports the Border Adjustment Tax, which is part of a bill pending in the House now. The bill is a massive overall of the tax code that would eliminate almost all itemized deductions for corporations and individuals, except the home mortgage interest deduction and charitable contributions.

The corporate tax rate would fall from 35 percent to 20 percent.

The BAT has many critics and raises many concerns for U.S. businesses, particularly retailers, who are dependent on imports. And though Trump made comments during his campaign that indicated he might look favorably on it, he's made comments since taking office that express concern about the proposal.

“Under the border adjustment concept, if somebody is making a motorcycle or a plane in our country, they’re getting a credit for the plane they make before they send it over to wherever it’s going,” he said. “And you don’t need that plus lower taxes and everything else.

"And it's too complicated. They get credit on some parts and not other parts. Where was the part made? I don’t want that. I just want it nice and simple.”

As you might expect, import-dependent businesses, such as large retailers, are fearful of the BAT. They argue they make nothing themselves to export to offset the expense of the tax on the goods they import to sell to their customers. JCPenney CEO Marvin Ellison said the BAT would make profitability nearly impossible for his company, at least in the near term.

"It takes our tax structure, as an example, from roughly a 34-percent corporate tax to over 170 percent," Ellison said.

Consumer prices, he said, would go up 20 percent.

"That's simple math."

Some economists think it's not that simple.

It's possible, some say, that the rise in the value of the dollar will balance the cost adjustment on imports and exports, or wages and prices rise together and consumers don't feel the pinch.

That's what Collins said he believes.

Pete Zeliff, owner of p.w. minor, when talking more generally about tariffs, said he believes things will work out in America's favor because of the strength of our economy.

"Tariffs may drive up prices, they may not drive up prices," Zeliff said. "What they will do is get more people to work where labor rates will go up and more people will be able to afford to buy everything. We will start manufacturing more and more here and prices will go down because our efficiency will be higher. Instead of 80 percent of our products made overseas, 80 percent will be made in America, so you will see prices go down."

Where a BAT makes sense -- if your goal is to tax all imports and exempt all exports, the BAT makes that easier to do. There's no car on the road today that was all made in Japan or in Mexico or the United States. Parts and supplies come from all over the world. A car assembled in Mexico contains many parts, up to 40 percent in some cases, that were manufactured in the United States. A BAT makes it easier to track which pieces get taxed and which don't instead of trying to figure out what portion of a finished product counts as imported and which should be considered American made.

A potential problem with the BAT is that would make things more expensive that simply can't be produced in the United States. You will pay more for chocolate and coffee, and since U.S. waters don't produce all the seafood Americans consume, we rely on imports, therefore seafood prices will rise.

Tequila comes from Mexico and while some avocados are grown in California, not enough to meet customer demand. Without margaritas and guacamole, a lot of Super Bowl parties could be ruined.

Collins said he understands Constellation Brands, based in Victor, is concerned about importing Corona from Mexico if the BAT goes through.

"They say you can't make a Mexican beer in the U.S., therefore it should be exempt," Collins said. "Should there be an exemption? If you put in one exemption, somebody else is saying, 'what about me? what about me?' and then it all falls apart. You don't have a 20-percent tax rate. You have a 34-percent tax rate. Don't count on any exemptions."

The big thing about the BAT is it's a big unknown. It's never been tried before. It's not clear that it will mean higher prices for consumers or if a stronger dollar will offset the adjustment. It's not clear it will raise as much revenue as Republicans hope year-after-year or if it will create more jobs in the United States or if it will even lower the trade deficit. What it is is a giant experiment with the U.S. economy and that excites some economists. They get to see in real time, in a real-world setting, how economic theory works.

Meanwhile, we don't know yet whether the BAT will even become law. The White House has not endorsed the plan and support is far from solid in the Senate. The administration does seem to think it can strong-arm trading partners into buying more U.S. goods, even if the prices are higher than what might be available from other suppliers.

All of this puts a lot of uncertainty around key parts of the U.S. economy, and business managers tend to prefer certainty when planning how they will run their businesses But the local business leaders we spoke to weren't particularly unsettled by the current transition.

"At this point, that uncertainty doesn't affect us," said Jeff Glajch, vice president and CFO for Graham Manufacturing in Batavia. "If one of those things were to suddenly result in a 35-percent tariff, that could cause some angst in the short term, but we tend to think that anything like a trade war would be short lived. Both sides would realize how harmful it is to both sides and they will come to the table."

Collins, himself a businessman, said he understands the need for certainty and that there may be some turmoil that goes with changes, but in the long run, local businesses will be better off.

"We're trying to move this fast, this tax reform piece," Collins said. "We want to get it done in 200 days, not three years. I acknowledge that there is some uncertainty and that is unsettling because people don't like uncertainty. In the meantime, you've got your customers and you make your product and you go home and worry a little bit. But it's all good news on the horizon, so maybe you go to bed and dream in multicolor."

Previously: