It can be said that housing authorities such as those under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development provide safe and affordable dwelling places for millions of low-income people in need.

But it also is true that these quasi-nonprofit enterprises benefit from their tax-exempt status, giving private landlords cause to question the fairness of the framework by which they exist.

You can draw a line from the preceding statements to the Batavia Housing Authority, a four-location government agency that offers HUD-subsidized apartments for senior (62 and older) and disabled tenants.

The BHA, which by New York State law is exempt from paying property taxes, receives subsidies from HUD to bring the monthly rent closer to the market rate and also receives periodic federal grants to help with renovations and maintenance across its buildings.

“The Batavia Housing Authority exists to provide safe, healthy and affordable housing for people who cannot realistically afford market rent,” he said. “The average rent collected is around $358 right now, and the federal subsidy is about $182 per apartment. Those amounts cover our monthly expenses, but our aging infrastructure requires some capital investment for the organization to be viable long-term.”

Recently, the BHA received a federal capital grant for $377,000 for renovations, including electrical systems and elevators, Varland said.

“Our margins are very low and it’s hard to stay efficient,” he said. “The capital grants that we apply for and (periodically) receive are vital. We wouldn’t be able to stay in business without them as half of our people can’t use the stairs.”

Varland describes the BHA as a “standalone government entity” that has entered into a Payment in Lieu of Taxes agreement with the City of Batavia that enables the housing authority to pay about 75 percent less in property taxes than what a nonexempt organization would pay.

He said the PILOT has been in force for many years, likely back to when the buildings were finished in the early 1970s.

The apartment complexes on South Main, Edward and MacArthur are three- and four-bedroom townhouse-style units for households of three or more people and, currently, all are full, Varland said.

Varland said the BHA owns its own properties with HUD having a controlling interest. Monthly rent is based on 30 percent of a tenant’s adjusted annual income (or 10 percent of the gross income), with maximum income limits depending upon household size.

Current rents for studios, one- and two-bedroom apartments include cable and utilities, and range from $490 to $675. He said that some people with little or no income pay as low as $50 per month in rent.

Three- and four-bedroom apartments are priced at $593 and $611, respectively, with a utility allowance deducted for those on subsidized rent.

According to the New York State law, municipal housing authorities that are project financed or aided by the federal government or municipality, not by the state, are exempt from property taxes but can be subject to special assessments, levies or PILOT agreements.

In the case of the BHA (actually classified as the City of Batavia Housing Authority by the Genesee County treasurer’s office), the PILOT paid to the City – and then disbursed to the county and Batavia City School District – is approximately one-fourth of the amount paid by a nonexempt organization.

Photo at right: BHA Case Manager Heather Klein, left, with 400 Towers resident Brenda Boyce.

For the fiscal year ending Dec. 31, 2020, the BHA sent a check for $64,879.74 to the City clerk-treasurer -- $14,638.65 to the city, $15,409.33 to the county and $34,831.76 to the school district. That’s 23.5 percent of the full amount of $276,539 based on the assessed value of the properties ($6.5 million) and the total tax rate of $42.54 per thousand of assessed valuation.

“We pay a PILOT every year and that’s an agreement when the housing authority was formed,” Varland said, noting that the buildings were finished in 1970 and 1971. “The formula is based on what we take in and some of our utility expenses that come off. It’s not insignificant – about 5 percent of our annual budget -- but it’s also not based on the full value of the properties.”

Genesee County Manager Matt Landers said he looks at it as a “glass half full” proposition.

“The pay a PILOT but, at the same time, they are a quasi-governmental nonprofit-type agency. So, if you think about it, other nonprofits might not pay any property taxes – churches, GCASA, Cornell Cooperative Extension,” Landers said. “I’m glad they’re paying something rather than nothing at all.”

BOARD OF DIRECTOR OVERSIGHT

While the BHA properties are not owned by the city, the city manager does appoint citizens to a board of directors that provides oversight.

“We advise Nate in the direction we think is best for the housing authority,” said BHA Board Chair Brooks Hawley, who has been part of the committee for about 10 years. “At our monthly meetings, we look at the budget, address resident concerns and come up with solutions to any issues as a team.”

A current county legislator and former City Council member, Hawley said that since the rents are less than market rate – even with the subsidies, the grants from HUD “help us out with things like elevators and big projects that (private) landlords usually don’t have in a residential home.”

“We have four properties and we try to keep them up and not have them depreciate to where we’re putting huge money into it.”

The current board consists of a chairperson (Hawley), vice chair (Roger Hume), treasurer (Tammy Hathaway), secretary (Teresa Van Son), City Council liaison (Al McGinnis) and two residents (Don Hart and Jason Reese).

Varland said that the board frequently deals with compliance and regulatory matters, and sets policy that aligns with regulations at all levels of government.

“Public housing authorities are some of the most regulated agencies around,” he said. “Regulations are in place for a reason, but it does require a lot of work to keep up – especially with a small staff like ours.”

PRIVATE LANDLORDS: IS IT FAIR?

The Batavian contacted two property owners with numerous houses and apartments in Genesee County, and both agree that the Batavia Housing Authority, with its subsidies and improvement grants, have the upper hand when it comes to finding qualified tenants.

“It’s tough. I understand that there is a need for supportive housing for a lot of tenants, based on income and need, but for us, there’s no PILOT or anything else on our properties,” said Duane Preston of Preston Apartments LLC.

“We pay the full tax amount and what hurts the smaller guy is when they (BHA) get $200,000 per apartment for renovations – cabinets, bathrooms. We would love to come into that kind of money for our properties, but we can’t as we’re based on market rate rent.”

Preston said that he does have tenants that get reduced rent based on their Section 8 status (where they submit a voucher for about a 10 percent discount off the average rental market rate for the area).

“The maximum for a one bedroom in that case is $710 with everything included, $850 for a two-bedroom and $1,050 for a three bedroom,” he said. “They just raised the rates on all of those.”

He said that it takes about four months of operations for the average landlord to cover taxes on the property – “and that’s before you figure in your mortgage interest, water bills, utilities and other things that you have to cover.”

When told that the BHA is a standalone entity that owns its properties, Preston asked, “Then why are they getting a tax break? Why doesn’t everybody get a tax break then? I thought it was owned by the City of Batavia, and if that isn’t the case, that’s definitely not fair.”

Preston also questioned why those BHA apartments couldn’t be offered at market rate and be subject to the Section 8 guidelines.

“And it’s kind of a suck on city taxes,” he said. “The city is paying fire department, police department, whatever, and it used to be garbage pickup. Luckily, we’re out of that business now. Still, it’s a suck on the city and we’re not getting the full taxes out of it. It’s a double whammy.”

BHA IMMUNE FROM RISING COSTS?

Jeremy Yasses of JP Properties said he feels that the BHA is immune from rising taxes and property assessments.

“In today’s day and age when budgets are tight for municipalities and taxes and assessments are being raised, it’s not affecting the Batavia Housing Authority. How fair is that to the common folks who work every day and their assessment goes up, their taxes go up and their cost of living goes up?” he said.

Yasses said he finds it hard to believe that the Batavia Housing Authority isn’t making a profit.

“You can’t tell me that they break even every year,” he said. “Why are we allowing them to be subsidized? Why did they just get all of those grants to update all their apartments, and society wants us to update ours, and we do it one at a time when we can. They can do all of them, all at once. And that’s not fair.”

He also said that if the BHA is indeed a federal government-run entity, the City of Batavia should have nothing to do with it.

“Why does the city have any say about what’s going on there?” he asked. “No one checks in with me to see how Jeremy Yasses and JP Properties is doing.”

VARLAND EXPANDS UPON GUIDELINES

Varland explained that the BHA is under Section 9, which he called a separate funding stream from Section 8 with separate rules.

“The way Section 8 works is that low income individuals apply for Section 8 and they get a voucher for rent. They can take that to a private landlord,” he said. “With Section 9, we’re responsible for all the compliance and have a high level of oversight.”

He said the oversight comes from the city’s board of directors, but the major player is HUD.

“We’re not city employees, it’s just that the city is the jurisdiction because we’re located within the city limits,” he said. “There’s two ways to look at it: If HUD says jump, we jump; if the city says jump, we’ll have a conversation about jumping. Still, we want to make sure that partnership is strong.”

When asked what would happen if the BHA were to dispose of its properties to an unrelated entity, Varland said the transaction would have to be approved by HUD and for the fair market value.

“It would also have to be used for affordable housing,” he said. “Basically, the mission of the organization (and its property) needs to be preserved.”

400 TOWERS: A SOCIAL EXPERIENCE

Varland said just about all of the 148 apartments at 400 Towers are rented, but two are coming open soon.

“Our wait list is pretty short, so now’s a good time to apply,” he advised.

He said the facility at the corner of Swan and East Main provides a “social experience with everything in one spot.”

“You move in and you’re ready to go. Those studios are here at 400 Towers, where we have trash chutes, the mail comes inside, a snack shop, some meals that resident volunteers provide at low cost, activities, and a case manager on site to connect to resources,” he said. “And we just opened a fitness center and a library."

The executive director said BHA is “stable” at this time, but there have been times when the HUD allowance has not been enough.

“It allows us to continue operations but we haven’t been able to keep the properties up,” he said. “Currently, we are able to maintain, but there are capital projects that need to happen in the next five years that we don’t currently have money for. But we’ve been able to keep the elevators working and keep roofs over the buildings – the basics – so we’re doing OK there.”

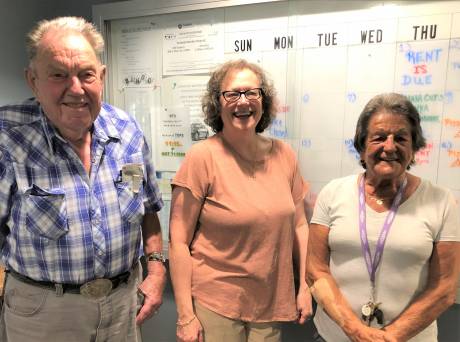

(Photo at right, Vicki Johnson, center, with 400 Towers residents Don Hart and Pauline Hensel).

He credited his staff for keeping things in order.

The administrative team consists of Vicki Johnson, housing manager in charge of recertification and property inspections; Abby Ball, leasing coordinator; Michelle Johnson, bookkeeper, and Heather Klein, case manager.

The maintenance staff lists four full-time employees and one part-time employee who are responsible for repairs and upkeep of all four properties. Varland said that he is looking to hire an entry-level full-time maintenance person.

COUNTING ON CITY PUBLIC SAFETY

Without its own security team, the BHA relies on municipal public safety agencies, Varland said.

“As far as security goes, we count heavily on the Batavia Police Department and Batavia Fire Department. They have been awesome,” Varland said. “They have been incredible supports and I don’t think that we could do this without them. We’re in a much better spot because of their support; it would be a struggle without them, plus our Genesee County EMS."

He said that 400 Towers has secure doors while the family units at the other locations each have separate entrances. A camera system also is utilized.

“I’ll put our maintenance staff up against any other anywhere,” he said. “They work really hard to make sure that doors, locks, windows are safe and secure. We make sure that everything is in good condition, and to the extent that we have money, we keep things durable and fresh.”

(Photo at right: Maintenance Supervisor Jim Green).

When asked about the frequency of evictions, Varland said that has not been an issue.

“There are a number of our residents who have had financial issues due directly to COVID – both here at 400 Towers and at the family units. We have been able to work with them directly to come up with repayment agreements. As long as we stay in communication we try to help these people manage their financial situations and we want to keep them safe,” he said.

Varland said management has worked out repayment agreements with tenants, working with partner agencies such as Independent Living of the Genesee Region, which offers an emergency rental assistance program.

“The federal government is very interested in making sure people stay safe in their apartments, especially during COVID,” he added.

MORE HOUSING IS NEEDED

Varland said he is well aware of the “definite need for housing” and said that need has changed over the years.

“We could probably do a separate article on that, bringing in the Genesee County Planning Department as we meet quarterly with the Housing Needs Committee,” he said, mentioning the significance of the Ellicott Station, Ellicott Place, Eli Fish and Main Street Pizza downtown apartment projects.

When informed that an 80-unit senior complex is proposed for Pearl Street Road, he said, that is the population that needs housing the most.

“The data that is out there, our population is aging and our family size – our household size – is declining. So, people need accessible, affordable, safe and smaller apartments,” he said.

Varland said he writes letters of support for those type of projects.

“I think they’re good for the city and the county, and don’t really think of them as competition for us,” he said. “We may lose people, and people come and go, however, if it’s good for the city and good for the county, it’s good for us, too. It makes it a better place to be and live.”