Part 8: Trump, trade and the local economy

Local Economic Development

This is part eight of an eight-part series on trade and how changes in policy might affect the local economy.

There's been a lot of talk about trade from President Donald J. Trump, but so far, no real action -- no new trade deals, no concrete action on tariffs or border adjustments. But just the idea that there might be some future advantage to manufacturing in the United States is already having an impact locally, said Steve Hyde, CEO of the Genesee County Economic Development Center.

"At least in the short term, this push, this effort to try and balance the trade profiles and make sure the U.S. is on an equal footing with the rest of the world, honestly, we're seeing an uptick in interest in manufacturers looking for U.S. sites, including direct foreign investment," Hyde said.

It's almost like all the work of GCEDC since Hyde became the CEO 14 years ago aligns with this potential new direction for the country. During those 14 years, GCEDC has been aggressive about creating build-ready industrial parks, from Gateway II, Apple Tree Acres, Buffalo East Tech Park, the Genesee Valley Agri-Business Park and WNY STAMP.

"I think there is still a wave of optimism going on about whatever relative changes may be coming," Hyde said. "The president is very focused on trying to beef up manufacturing in America and that's certainly helped our focus here on Genesee County to bring back manufacturing in both food and ag and in advanced manufacturing."

The president's potential policies just enhance GCEDC's efforts, Hyde said.

"There's a bit of a bubble and ramp up of interest in manufacturing products of late and siting new facilities and trying to bring back growth and manufacturing to the state."

Hyde said he's recently had specific inquiries from foreign investors in sites at Gateway II and STAMP, with a lot of activity around STAMP.

The plan is still to break ground on STAMP this spring, though there seems to be an air of uncertainty about the company expected to be STAMP's first tenant -- 1366 Technologies.

While 1366 has raised tens of millions of dollars in venture capital backing, has already signed contracts with foreign firms to buy its solar wafers, there is still a potential issue with the company receiving funding assistance from the Department of Energy.

The Trump Administration has taken steps that alarm some environmentalists concerned with climate science, but that has been mostly directed at the Environmental Protection Agency. Rick Perry, Trump's selection to head the Department of Energy, testified during his Senate confirmation hearing that he's had a change of heart on climate science and has come to accept climate change as a real concern.

"I believe the climate is changing. I believe some of it is naturally occurring, but some of it is also caused by man-made activity," Perry said. "The question is, how do we address it in a thoughtful way that doesn't compromise economic growth, the affordability of energy, or American jobs."

On the manufacturing front, as 1366 officials point out, if the Trump Administration goal is to increase U.S. manufacturing and U.S. exports, 1366 will be exactly that kind of company. At least initially, 1366 expects to export all of its solar wafers.

We asked Laureen Sanderson, a spokesperson for 1366, about the status of the project in light of the new administration and when we can expect 1366 to break ground on its local factory. Here's her response:

Yes, we’re factoring in the change in administration into our business plans. We expect the new administration will support U.S. manufacturing jobs and we’re looking forward to working with the team to do just that. At this time, I don’t have any additional details or timing to share but I will be sure to let you know as soon as we do.

Your trade questions are all excellent but we don’t want to speculate. We obviously support policies that support the global industry and its growth. We do not need clarity to move forward. One of the great things about the Direct Wafer technology is just how competitive it is, the cost reductions we allow for are unmatched and that positions us really well.

One of the possible trade policy changes is the Border Adjustment Tax. That would put a 20-percent tax on imports but make revenue derived from exports completely tax free.

"That would be a huge benefit for 1366," Hyde said.

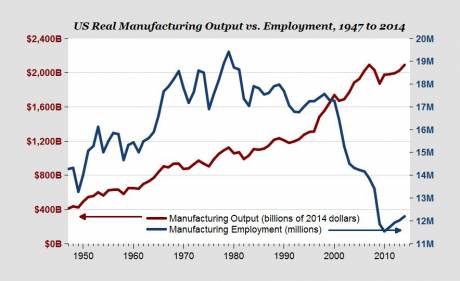

One of the criticisms economists have leveled at a potentially more protectionistic regime from the Trump Administration is that the United States simply doesn't have the supply chain any longer to support increased domestic manufacturing.

Trump's trade policy advisor, Peter Navarro, doesn't think that will be a problem.

“We need to manufacture those components in a robust domestic supply chain that will spur job and wage growth," Navarro said.

Hyde said with Genesee County sitting half way between Rochester and Buffalo -- the second and third largest population centers in the state and the second and largest export areas in New York -- along with all of the build-ready sites, the county is well positioned for any repatriating of a manufacturing supply chain.

"A lot of manufacturers want supply chain partners within an hour of their manufacturing site," Hyde said. "Some of the things going on at the Federal level has us well positioned to attract some of that supply chain, depending on how things unfold."

Like a good entrepreneur, Hyde is always optimistic. He never lets go of the big vision he has for creating jobs in Genesee County and he's excited by the activity he is seeing around not just STAMP but Gateway II and the other sites GCEDC has ready for new factories.

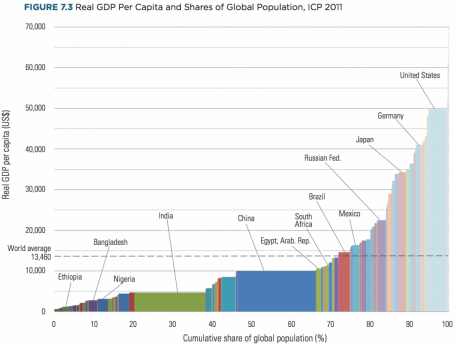

"About 5.6 percent of New York's private sector jobs come from employment at foreign-owned companies," Hyde said. "Foreign direct investment is a prominent part of New York's economy. With a focused policy at the federal level, advanced manufacturing is something we could see go up and that means good-paying jobs. Advanced manufacturing is the best way to build wealth in a community."

GRAPHIC: A rendering of what WNY STAMP might look like some day.