history

Guest Speaker Series: Lincoln’s Secret Visit

HLOM Guest Speaker Series: War of 1812 on Lake Erie

Opening Reception for WWI Exhibit at HLOM

Oakfield Museum Open Hours

New Exhibit at the HLOM- “A Century of Questions: The Linden Murders Still Unsolved”

Two members of GCC faculty team up to bring the past to life with 'Rudely Stamp'd'

If Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were alive today, what would they say to each other?

Genesee Community College associate professors Derek Maxfield (History) and Tracy Ford (English) are teaming up to create an imagined conversation between the two founding fathers in retirement.

The men had been close friends, but their friendship fell apart and they didn’t speak for 10 years," Maxfield said. “When they were both retired from politics, their friendship was renewed through correspondence."

Jefferson was in Monticello, Va., and Adams was in Quincy, Mass., when they began writing to each other.

“This conversation that we’re going to stage, while it physically never happened, we’re using the correspondence, to form what we say to each other,” Maxfield said, adding that the aim is to make Jefferson and Adams more human, to promote a better understanding of them both.

At 7 p.m. on March 7 at GCC, they will have an advance presentation of the program for the public. They will reading from a script at podiums, as a warm-up to work through the script.

Maxfield will be Adams; and Ford will be Jefferson in the program.

When Maxfield first read the correspondence between the historic figures, he wondered what they would say to each other now.

“If they did see each other face to face again, what would that look like?” Maxfield said. “That’s what we’re aiming for.”

The associate professors named the group after a quote from Shakespeare because they were looking for a unique name.

“We wanted it to have some history or literature flavor to it,” Maxfield said. “We came across this and it seemed perfect, because both Tracy and I are 'rudely stamp’d.' ”

"Rudely Stamp’d" has a kickstarter campaign to fund the costumes and props, located here. Maxfield said they want the most authentic-looking costumes for the program.

“We’re hoping to raise $6,000 before Dec. 25,” Maxfield said.

They hope to expand the group eventually, to include other programs, including an Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas debate.

Maxfield said he hopes to bring other living historians into Rudely Stamp’d.

“The idea is eventually to bring in select others,” Maxfield said.

Rudely Stamp’d is not a business.

“It’s not something we’re going to make money with,” Maxfield said. “It’s something we want to make available for anyone who is interested.”

Associate Professor Tracy Ford (submitted photo)

Associate Professor Derek Maxfield (submitted photo)

Free lecture at GCC Dec. 6 on creating 'illegal immigrants' in 19th century America

Press release:

Genesee Community College's History Club proudly welcomes the public to the Batavian Campus to hear Orleans County Historian Matt Ballard present, "Fear of the Unknown: Creating the Illegal Immigrant in 19th Century America."

The theme of immigration to the United States is a relative topic in current events, but the establishment of the "illegal immigrant" only dates back to the turn of the 20th century.

In the earliest years of immigration, Europeans were accepted without restriction, but an influx of new immigrants during the latter half of the 19th century raised concerns about potential impacts on American society. Uncertainty and unfounded fears created excessive restrictions focused on limiting access to specific ethnic/racial groups, religious groups, the disabled, the infirmed, and those likely to become a "public charge."

This lecture, the fourth one in the fall Historical Horizons Lecture Series, will take place at 7 p.m. on Dec. 6 in room T102 of the Conable Technology Building at GCC's Batavia Campus.

The lecture is FREE, open to the public and an RSVP is NOT necessary. The lecture series is sponsored by the GCC History Club and the Barnes & Noble College Bookstore.

Photos: Veterans Day in Le Roy

Veterans Day was originally known as Armistice Day, the day the war to end all wars ended, Nov. 11, 1918. After more wars, Armistice Day became Veterans Day, the day we honor all of those who served to defend freedom.

Today's ceremony in Le Roy included guest speaker Ret. USN Commander Robert “Bob” Kettle, who now lives in Seattle with his wife and 2-year-old daughter.

The 1984 Le Roy High School graduate spoke about the sacrifices Le Roy residents made during The Great War.

The honor roll includes:

- George K Botts, Private, Co G, 7th Infantry, 3rd Division. Killed in action near Fossoy, France, July 15, 1918. Age 23.

- Cecelia J Cochran, Nurse volunteer, U.S. Public Health Service. Died of influenza and pneumonia in a military camp hospital, Huntsville, Ala., Oct. 15, 1918. Age 24.

- Errol D Crittenden, Private, HQ Co, 312th Engineers, 87th Division. Died of pneumonia at Camp Grange-Neuve, Bordeaux, France, Oct. 15, 1918. Age 31.

- Thomas C Illes, Private, Co G, 74th NY Infantry. Killed when struck by a trolley in Buffalo, Sept. 8, 1917. Age 22.

- Edward L Kaine, Private, Co B, 59th Infantry, 4th Division. Died of pneumonia in a hospital at Aix-les-Bains, France, Nov. 9, 1918. Age 28.

- Patrick Molyneaux, Private, Co A, 59th Infantry, 4th Division. Killed in action near the Bois de Brieulles, France, Sept. 30, 1918. Age 29.

- Edgar R Murrell, Private, Btry D, 307th Field Artillery, 78th Division. Died of pneumonia and diphtheria in a military hospital near Winchester, England, March 29, 1918. Age 27.

- George F Ripton, Private, Co C, 3rd Provisional Battalion, Engineers. Died of influenza and pneumonia at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, Oct. 10, 1918. Age 28.

- Alvin A Smith, Private, Co A, 108th Infantry, 27th Division. Killed in action near Hindenburg Line east of Ronssoy, France, Sept. 29, 1918. Age 17.

- John R Wilder, Sergeant, 50th Aero Squadron, U.S. Signal Corps. Died of pneumonia in an Army hospital at Baltimore, Md., Jan. 11, 1918. Age 27.

Source: The County and the Kaiser: Genesee County in World War I.

Historians gather at GCC to debate controversy around Confederate monuments

Like human beings, it’s complicated, multifaceted and a work in progress.

Historians who gathered at Genesee Community College on Saturday to discuss monuments and statues of the Confederacy made that point clear.

Other issues emanating from that controversial topic were more opaque.

Should Confederate monuments be disassembled and put into a museum? Or stand as they are and “contextualized” by the addition of explanatory signage or a juxtaposing anti-memorial?

By what criteria do we evaluate the people honored? Are they more than their worst traits? Do they contribute to the public discussion beyond their role in the Confederacy?

While more and more Americans wrestle with those kinds of questions, by all accounts, the current debate is fraught with emotion. There’s a quick-tempered divisiveness that too often rapidly devolves into shouting matches or worse, culminating in the nadir at Charlottesville.

Derek Maxfield, Ph.D., GCC associate professor of History, brought together a three-man panel to weigh in on Confederate monuments. It was the last session in a day spent talking about the short shrift that history, especially local history, is getting in New York classrooms, the stifling trend of "teaching to the test," and disaster preparedness as it relates to safeguarding historical artifacts.

Speaking were:

- (Via Skype) Chris Mackowski, Ph.D., who lives just outside Frederickburg, Va., but teaches online as professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at St. Bonaventure University in Cattaraugus County.

- Michael Eula, Ph.D., Genesee County historian, who is a retired academic who spent 30 years in the California Community College system.

- Danny Hamner, GCC adjunct professor of History for the past 15 years in Batavia.

They cited a series of articles which have been published online at a site called "The Emerging Civil War,” which offers fresh and evolving perspectives on America’s deadliest conflict. (To visit, click here.)

Mackowski provided a launching point for the sake of the discussion at GCC. He penned an article from a free speech perspective for the Emerging Civil War series because it interested him as a journalism professor, and other authors had dibs on other aspects of the controversy.

“As soon as you start saying, ‘Take down that statue because it’s offensive to me,’ to me, that’s a First Amendment issue,“ Mackowski said. "Here you have artistic expression and people saying ‘That art is offensive.’ It’s always been my understanding that one of the purposes of art is to provoke. So, of course, in some ways it’s going to be offensive to some people.”

Eula said “I couldn’t agree more that art as embodied in these statues is by definition provocative. In fact, it should be provocative. First and foremost, we need to remember that when we look at these monuments, and the discussion surrounding them, we are talking about more than monuments.

“We’re talking about how we conceive of American history…of our civil society. I think each side engaging in the conversation needs to take a moment to try and understand the other perspective, the other side."

Hamner said that although he’s disturbed by the emotional response against Confederate artwork, he diverged with Mackowski on two points.

Firstly, the question of public art versus private expression.

He said he associates the First Amendment with personal displays of art: putting a Confederate flag on your porch.

“But when it comes to public art, to me it’s not a question of free speech, it’s a question of pure politics,” Hamner said.

Therefore, Hamner advocates having a true political process to work through so that opinions are heard and a “rationale discourse” can take place regarding each monument or statue on a case by case basis.

Secondly, whether there is “instrinsic value” in a work of art strikes him as “moving the goalpost a little bit.”

Hamner said the tougher question that does need addressing is: “Do these people have intrinsic values that we need to respect – outside of their association with the Confederacy?”

Mackowski, acknowledging he purposely wrote from the viewpoint he did because it was not covered by others in the online series, agreed with his colleagues.

As we wrestle with the notion of what makes somebody worth honoring, a fear – particularly in pro-Confederate quarters – is “Who’s next?” Mackowski said, and while some argue this is a slippery slope, he allowed that “we probably need to evaluate some of these other folks.”

What do these guys represent?

It was at this point that host Maxfield brought up the stark argument, in The Emerging Civil War series, proferred by Julie Mujic (pronounced “MEW-hick”), Ph.D., adjunct professor of History at Capital University in Bexley, Ohio.

She argues that Confederate statues commemorate treason and ought to be removed.

“To sustain Confederate monuments sends the message that it’s necessary to celebrate the effort, even when that effort was malicious. The monuments must come down. They represent inequality, oppression…”

Mackowski said Mujic’s stance strikes at the heart of the whole argument: "What do these guys represent?”

“As you know, the history of the war was rewritten as soon as the war was over. And instead of it being about slavery, it starts to be about ‘noble sacrifice’, ‘doing your duty’, and ‘honor’ and ‘states’ rights’.

“So today, a lot of people refuse to look at people who served with the Confederacy as being traitors, but in fact, that’s what they were. … So do you honor that or not? That’s a very important question that we don’t have a common context for.”

Hamner has a problem with both Mujic’s argument AND the defenders of the monuments for essentially the same reason.

He cites a catch phrase, even used by President Trump in a tweet, that “You can’t change history.”

He said people tend to think of the past as objective, factual and unchanging; our historical interpretation of that past as either right or wrong.

The problem is, that “implies that the process was somehow supposed to end.”

The deal is, reinterpretation of the objective truth is going to happen with every generation, as knowledge evolves, more facts come to light, consensus migrates.

As they all conceded, historians and the citizenry can’t change the past, but the interpretations of the past must be constantly requestioned.

"I’m always struck by the curious statement that ‘We’re revising history'," Eula said. "My reaction is that ‘History is always being revised.’ "

Having said that, Eula noted that at the time most, if not all, of the statues and monuments were erected, there was no national debate about it, no consensus.

“We need to keep in mind the question: Is the removal of a monument erasing history or merely calling our attention to what is now a different interpretation of that moment in time?”

Forgotten nearly always in these discussions, Eula pointed out, are the poor whites who had not been supportive of the Confederacy from the get-go.

A whole year before the North passed a draft law forcing mandatory armed service, the Confederacy did so, which tells historians the South was not getting the numbers of volunteers for The Lost Cause that many today would like to imagine.

And the slave-holding elite, later the pardoned ex-slave-holding elite, still got the run of the place after the war.

That meant former slave owners got to become the local bankers, and pass vagrancy laws, which continued the bondage of freed men, Eula explained.

This informs today’s understanding of the time in which the statues came to be.

“My point is that it isn’t simply a straightforward proposition as to whether these statues are works of art protected by the First Amendment; whether or not there are contemporary implications for race relations in our own day.

“These are products of a specific historical moment in a specific part of the country.”

Impact Beyond the Confederacy

Eula also said many of the Confederate generals had no significance beyond their military career. That raises the question, for example, does this form a slippery-slope logic for the removal, say of the Washington Monument? No, Eula argues, because although Washington owned slaves, “his significance lies in his contribution to the construction of a new nation.”

“These (Confederate) monuments are dedicated to the memory of an elite South…seeking to destroy the United States in the name of slavery…that was as busy trampling on the rights of poor whites as it was on the slaves."

And, if the decision is made to get rid of a monument, which whether you like it or not is a “historical document,” then the process to do so must abide by some local, identifiable political construct.

To just tear down a monument, Eula said, is akin to someone walking into the Genesee County archives and saying “Well, I don’t like what’s said on this particular piece of paper, therefore, I’m going the shred it.”

“Just like for any other historical document, we have to find a way to preserve these. Whether or not they should be preserved in a public space, that’s another issue...

“These are the kinds of issues that need to be sorted out before we can make any final decision on whether or not any particular Confederate memorial stays or is replaced,” Eula said.

The operative phrase is “particular piece,” says Mackowski.

“To look at Confederate monuments as a big, monolithic one-size-fits-all sort of issue is absolutely the wrong way to go about it,” Mackowski said. "But because tempers are flaring and emotions are high, that’s sort of how people are approaching it.”

Instead, a lot of questions should be asked to inform a reasoned debate, say historians.

Who was the monument put up to honor? Why was it put up? Who put it up? When? What was the intent?

Moreover, a statue of Stonewall Jackson is a very different thing than a statue in the courthouse square that honors the local county boys who got drafted into a regiment and sent off to war.

Plus, consider that community values change, and over 150 years, they change a lot.

A book by David Lowenthal called “The Past is a Foreign Country – Revisited” describes, the panelist said, how today’s values differ vastly from those of yesteryear.

So, it behooves people today not to try and look at history through the lens of “presentism.”

“I think we’re not really talking about history at all when we talk about these monuments, we’re talking about memory,” Mackowski said.

The Sorry State of Historical Literacy

This observation prompted Maxfield to mention a problem he calls “historical literacy,” or more precisely, the lack thereof.

“I don’t want to come off as elitist about this, but the fact of the matter is we are spending less and less time in the public schools teaching history,” Maxfield said.

“We’re shoving it out of the curriculum and, in fact, Confederate history in particular, CANNOT be discussed in some Northern states.”

And vice versa; Texas comes to mind.

“That’s an unhealthy phenomenon, when you can’t look at the other side of an argument,” Maxfield said.

Meanwhile, Hamner is concerned that while people scurry to make sure history’s getting correctly written and that context is being correctly construed, there’s a gaping window open for some people to ram their political agendas through.

“One only has to look at the way Donald Trump defended the artistic value of these monuments, when he has a l-o-n-g history of development in New York City of tearing down artwork after artwork to make room for his projects.”

To wit, the construction of Trump Plaza is said to have resulted in the destruction of an Art Deco-style store that featured windows created by Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali.

None other than the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City waited in eager anticipation of what was supposed to be the fantabulous donation of massive Art Deco bas-relief murals from that store, only to find they had been knocked down and destroyed by Trump’s crew so as not to prolong the project by a week and a half.

The point?

“We have to be very careful that we are separating people who are using some very valid argument to shield ulterior political agendas,” Hamner said, adding “…I would hate to see a very important, intelligent conversation like this being used in a way as a shield for what I consider very, very base intentions.”

It also is not helpful that the general public does not seem to understand what the discipline of history is all about.

“A lot of what historians do is really philosophy,” Maxfield said. “Until we have the opportunity to teach more critical thinking and encourage more exploration, I’m afraid what we‘re doing, especially in the public schools, is narrow and narrow and narrow.”

Facts and Sensibilities

It’s important to remember, too, Mackowski offered, that in history, a set of facts does not equal a set of facts. Two plus two does not equal four when you are dealing with facts in history, he said.

Fact: The Union Army moved in to occupy Fredericksburg in the spring of 1862.

But that fact is viewed vastly differently by two diarists who wrote about it. One was a member of the social elite who wrote about it being this great calamity; “The Yankee invaders are here; this is awful.”

An emancipated slave saw it differently. He wrote “This is the greatest day of my life. This is the greatest thing to ever happen.”

Thus, adding together different historical perspectives over the span of a century and a half is something that can’t be “summed up” tidily.

“Before this degenerates into mindless philosophy,” Maxfield told Saturday’s attendees, garnering some comic relief, how about considering one solution offered by a historian: Leave all the monuments as they are, but just improve the interpretive signage.

How other nations have addressed the issue of historical monuments was something that Eula explored when asked to participate in the GCC panel.

“The whole issue of holocaust memorials was an obvious one” to look into, he said.

One approach he found was memorials constructed next to other memorials with different interpretations attached to them.

In the United States, for example, you could put up: a monument next to the existing one that denotes the number of slaves murdered during their enslavement; or the number of soldiers who were murdered at the Confederate prison of war camp at Andersonville, Ga.; or “the number of poor whites who couldn’t buy their way out of the draft, who didn’t support the planters’ war, and who paid for that with prison sentences,” Eula said.

Coming up with a county-by-county count of the dead, might be a way of “softening the effects of the monuments with regard to those who find them objectionable,” the official county historian said.

At this juncture, Hamner said he sees agreement about the panel’s strategies and tactics; but it comes down to his original point: the need to separate the historical element from the political one.

“I would hate to take The Lost Cause interpretation monument and then simply encase it in a new interpretation and say ‘That’s the official interpretation. Now it’s done.’ "

There is no "One Conclusive Truth"

Hamner's desire is to protect the PROCESS of public history, not the monuments themselves.

“If the political process in that community says ‘We’re putting it in a museum.’ Ultimately, I’m for that," Hamner said. "What I’m really worried about is understanding the particularities of each monument, maintaining the process of investigation, and the willingness to revise our thinking – every generation, every person.”

Which begs the question, in Eula’s mind, as to WHY we necessarily have to have ‘ONE CONCLUSIVE TRUTH’?, he asked, slapping his hand on the table as he spoke each word.

“The minute you do that it leads you down, historically, a path of dogmatism that tends to shut down democracy, that tends to shut down the expression of free ideas.”

What if we as a society never have agreement?

“So what! … Why can’t we agree to disagree and have a civil discourse?” Eula asked.

The absolute declaration of what the correct interpretation is, was called totalitarianism in the 20th century, Eula reminded the audience.

Remember, there was a time when you were either for or against McCarthyism. You were either for or against the United States entering the purported "war to end all wars,” “The Great War” -- World War I.

“That’s when a lot of innocent people get hurt and killed, for reasons to me that are absolutely senseless,” Eula said.

Mackowski countered with a “get real” argument.

Philosophizing aside, and since the notion of “contextualization” of Confederate monuments is so kosher among historians, Mackowski wanted to play devil’s advocate.

“If you’re driving down Monument Avenue in Richmond (Va.), it’s basically an auto park,” Mackowski said. “Who’s able to stop at one of those traffic islands in the middle of traffic and read context about Stonewall Jackson or Jeb Stewart or Jefferson Davis?”

Context is actually difficult to pull off in some places, he noted, and maybe even if you could pull it off, does it really match up to these giant men on giant pedestals?, he asked.

And let’s say you decide to leave it in place, what about vandalization?

To that, Maxfield chimed in with something that a historian from Texas A&M University had to offer, and that is that location does matter.

Andersonville, for example, is cited as the South’s version of a 19th century concentration camp; a place where 11,000 to 13,000 federal troops meet a grisly end under brutal conditions.

If a monument stands in a place such as this, it should be kept there, the scholar argued, even if publicly funded, because going TO that site or a battlefield is voluntary. The same cannot be said for someone who must drive past a statue that offends you every day to get to work and there’s no other route to go; that’s involuntary.

Plus, on a battlefield, historians and/or Park Service employees are there to help with knotty questions and interpretations, right?

Wrong, says Mackowski, in fact Park Service employees have largely been silent on the issue. Because taxpayers pay their salaries, they can’t really delve into it.

Some of the people best equipped to comment on this discussion have their hands tied because of politics, Mackowski said.

Nor has academia been free from constraints, Maxfield noted.

Removing monuments on a battlefield, which is essentially a giant cemetery, raises “other complexities,” according to Eula, who stressed the need for balance.

“Because we have people there, regardless of our own idealogical beliefs, who ended their life there, most likely involuntarily.”

He went on to recall how memorials to Stalin and Lenin came down in Eastern Europe in the middle of the last century.

Growing Dissent

“My point here is that, as much as it pains me to say this, there could be enough popular dissent out there regarding all these statues that no amount of discussion or legislation could change.

“It could be that our own society has so changed in the span of the last two generations in particular, that there is this huge upsurge demanding a removal of some of these monuments in the way that we saw in the Soviet Union with regard to Stalin.

“And I’m not convinced historians, even the most well intentioned, are really going to have a whole lot to say about this.”

This perspective prompted Mackowski to ask why this moment, why now?

Eula maintains that some of this popular dissent has been growing for a long time, back to the 1960s and the feelings spurred by the morass of the Vietnam War.

“It’s what I started off by saying – this is not simply about Confederate monuments,” Eula responded. “There are deeper currents here at work, and these didn’t begin recently.”

The groundswell of attention paid to the subject these days could, in part, stem from harsh “economic realities” many people face, which historians have largely been insulated from.

This means that “some of our discussions are frankly going to prove irrelevant” because they are not, rightly or wrongly, in alignment with what the populace is feeling, thinking or demanding, Eula said flatly.

Hamner said, on one hand, there’s this sort of academic/historical question of how best to contextualize Confederate artwork. Then on the other hand, there’s a deeper human question of WHY historians do what they do.

The thing that matters most of all, he said, is that – regardless of whether a decision is made to keep or do away with a monument – that a process is followed to get to the decision.

Hamner contends that the camp that says "Leave it alone. Don’t touch them" is made up of people who want to freeze time and not confront the complexity of heritage.

They are reducing human beings to their best qualities – like bravery – “a disembodied sort of character trait.”

But the opposite camp is also reductionist – making complex humans villains and the epitome of their worst characteristics.

For an example of the former, Mackowski showed a picture of the statue of Stonewall Jackson at Manassas National Battlefield Park in Prince William County, Va. (See inset photo above.)

He said Jackson is made to look like “Arnold Schwarzenegger on a Budweiser Clydesdale" … like this God of War – a horseman of the Apocalypse. In reality, Jackson was slight, modest and “would have been appalled to be portrayed this way.”

In other words, monuments are less about facts and more about “how people want to remember the Stonewalls.”

What About Bias?

A student asked the panel, “So if interpretation is the key solution, how do we select the accurate interpretation for each monument without being biased?”

The panel's collective wisdom: Finding “the objective truth” and “the right interpretation” is doomed.

Rather it is consensus itself, by interpreting and reinterpreting, that will painstakingly get you “closer and closer” to what the pluralistic outcome ought to be.

Yet Maxfield said even that is elusive because “there are progressive historians that believe progress in humankind is possible – you get closer and improve – but other historians disagree with that." That dichotomy also shapes interpretation.

Eula said he thinks it’s not possible for a historian not to be biased. So you be as objective as you can be by acknowledging your bias, “your theory.”

Since “just the facts” are not the whole story, “you look at evidence based upon your starting point. But the responsibility of the scholar is to let the audience know: This is my starting point.”

Before you can get to an interpretation of a monument, for example, you have to get people to “understand that history is relevant,” Mackowski replied.

“Unless you can get people to understand that history is not what happened in the past, but rather why the past is influencing what is going on RIGHT NOW, people aren’t going to get to that (new and improved) interpretation.”

It’s that whole issue of general historical illiteracy that Maxfield had lamented earlier.

To make meaningful headway, people have to have discussions, the historians said, not ongoing yelling matches.

“Or 140 characters of saying ‘You’re wrong!’ " Mackowski concluded.

Local conference to discuss practice of history in the classroom

Those who authored common core requirements for schools, de-emphasizing local history, stressing standardized tests and rote memorization, serve to preclude the joy of discovery and independent thinking, said Genesee County Historian Michael Eula, Ph.D.

Visiting museums or archives nurtures the joy of discovering and independent thinking, Eula said.

A local history conference at Genesee Community College on Saturday in Batavia, will explore disaster planning, the state of history in Genesee County, teaching history in classrooms, and Confederate monuments.

Eula will be doing a presentation at 9:15 a.m. on the state of history in Genesee County. Presentations run throughout the day until 2:30 p.m. in room T102 of the Conable Technology Building, at GCC’s Batavia Campus.

Eula said after three decades of historical practice, he has been continuously awestruck by the levels of commitment, talent and devotion that those in the county display in their quest to discover the history of Genesee County.

A topic in Eula’s presentation is about the practice of history in the classroom.

“[It] is not always connected to the purity of purpose and the energy articulated by our County’s public historians,” Eula said.

History teachers have the task of synthesizing the local history of the county, Eula said.

“Young people – our future – need to be brought more fully into our historical conversations,” Eula said.

Eula said he believes local schools are under pressure from state and federal officials to teach materials that are consistently national and international.

“The tone that is set is that somehow local history has a small part to play in an understanding of how contemporary society came into being,” Eula said.

One consequence of the common core is an erosion of a history, tending to build pride in one’s past, Eula said.

“[It’s] the kind of self-esteem that makes one proud of their community,” Eula said. “This consequence may in fact tell us much about the ideological motivation of those on the state and federal level who seem to view local history with suspicion,” Eula said.

Public and private historians are welcome to attend the conference, as well as history buffs of all ages. The conference is being sponsored by the Genesee Community College History Club and the Genesee County Federation of Historical Agencies.

A presentation called “Tracing Lineal Heritage/Daughters of the Revolution,” will be at 10:15 a.m., a panel discussion for disaster planning for historical organizations and museums will be at 11 a.m., and a discussion considering Confederate statues, memorials and symbols will be at 1:15 p.m.

Derek Maxfield, GCC associate professor of history, History Club advisor and president of the Genesee County Federation of Historical Agencies, said in a press release, that they put together a day of interesting programs that should appeal to a wide variety of history-minded folk.

“I am especially interested in the session on disaster planning and the panel discussion about the Confederate monument controversy,” Maxfield said.

Historical agencies and museums are invited to set up displays for visitors to browse.

Registration for the event is $25 and includes a boxed lunch. If you wish to attend sessions without lunch, registration is $12. Those wishing not to have lunch may register the day of the event and pay at the door.

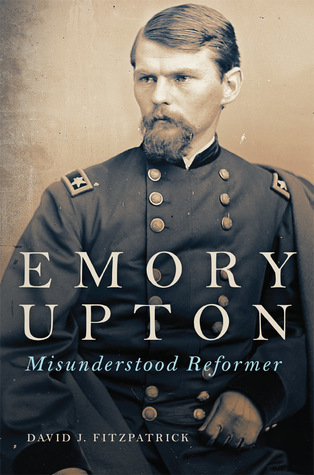

New book corrects the record on Emory Upton's attitude toward the military and the republic

Upton distinguished himself during the Civil War in battles at Salem Church, Spotsylvania, Opequon Creek, and in other engagements.

"He was one of the outstanding regimental commanders of the war," said Fitzpatrick, who teaches at Washtenaw Community College in Ann Arbor, Mich. "He had a tremendous tactical success at Spotsylvania."

The fact that Upton is still discussed among military leaders and those interested in military history, though, has more to do with his ideas and what he scribbled on paper than what he accomplished on the battlefield.

Some of what Upton wrote has led to more than 50 years of the Army officer being misunderstood and misrepresented, though, according to Fitzpatrick.

In the mid-20th century, Upton gained a reputation as a Prussian-inspired militarist with little respect for democracy. That assertion doesn't fit the documents in the historical record, Fitzpatrick contends and he makes that case in his new book: "Emory Upton: Misunderstood Reformer" (University of Oklahoma Press).

"Upton is an important figure in U.S. military history," Fitzpatrick said. "He's a figure a lot of people don't know about."

While you might expect a book steeped in military policy and battlefield strategy to be dull and dry, Fitzpatrick has written a story that is fascinating and at times even a real page-turner. Upton was a man both of action and ideas dealing with some of the most important considerations that would shape history after his death in 1881.

Batavia's Civil War hero was born to a farming family in Genesee County Aug. 27, 1839. A devout Methodist and a fervent abolitionist, Upton attended the era's most famous integrated college, Oberlin, before being accepted into West Point, graduating eighth in his class in May 1861 (The only blemish on his West Point career was a fight with a Southern cadet who made remarks behind his back, hinting that Upton had sexual relations with a black girl at Oberlin. Upton took offense and when the cadet wouldn't explain himself, Upton challenged him to a duel that became a fight in a West Point dorm.)

After the war, Upton was sent on an 18-month tour of Europe and Asia to study the military tactics of countries on those continents, especially Germany. When he returned he wrote "The Armies of Europe and Asia," "A New System of Infantry Tactics" and "Tactics for Non-Military Bodies" (aimed at civilian associations, police and fire departments); and more than 20 years after his death, his unfinished work, and most important book, "The Military Policy of the United States," was released by the War Department.

There were aspects of the military position in Germany that Upton admired and these served as a basis of Upton's recommended reforms to the U.S. military. This led to charges among critics that Upton and his like-minded reformers were trying to foist Prussian militarism on the United States.

These charges were amplified with the publication of a book in 1960 by Russell Weigley, "The American Way of War," which traced the intellectual development of military strategy and policy, and Stephen Ambrose, with "Upton and the Army," in 1964.

To Fitzpatrick, the real offense to Upton's legacy was the book by Ambrose. Weigley can be forgiven for getting Upton wrong, Fitzpatrick said, because he wasn't writing a biography, but Ambrose's biography began as his dissertation (and was published verbatim in book form).

"Ambrose was doing a biography but didn't dive into the sources he should have," Fitzpatrick said. "I think Ambrose read Weigley and just decided to echo Weigley."

Fitzpatrick poured through the letters of Upton, among other documents, with help from Sue Conklin, who at that time was Genesee County's historian, and the Holland Land Office Museum (Fitzpatrick was provided a CD of images of all the Upton letters in the HLOM's collection).

And going through Upton's letters isn't an easy task.

When arranging a visit to the County's history department, Fitzpatrick told Conklin his topic and Conklin told him, "Have you seen his handwriting?"

"No," Fitzpatrick admitted.

"You might want to consider another topic," was her droll response.

Fitzpatrick doggedly stuck with Upton's letters, however, which provided insight overlooked by Ambrose into Upton's thinking on military planning and civilian government.

Upton believed the Union could have ended the Civil War before the close of 1862 (it wouldn't end until 1865) if the military had been led by more competent officers, had been better equipped, staffed with more men, and Gen. George McClellan hadn't been hampered by interference from civilian bureaucrats, notably Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Even though Upton had been critical of McClellan during the war, his animosity toward Stanton was even deeper.

"He starts to twist history to make Stanton into the bad guy and McClellan a genius," Fitzpatrick said. "He wrote (in a letter) that he was having a hard time with 'the McClellan question,' as he calls it. It is really causing me trouble, he said. I hear him saying that he's having a hard time making the facts fit the story. Stanton was a meddling failure, not that it was McClellan himself who caused his failures."

The focus on Stanton, however, Fitzpatrick concludes, isn't because Upton is against civilian leadership of the military, but rather a concern that a war secretary with too much power could potentially use that position subvert the country's republican form of government.

Upton's reform ideas included mandatory retirement at age 62 for officers, rotation of officers between artillery and infantry, promotion on merit rather than seniority, and more training for officers.

While Upton was distrustful of democracy -- like Alexander Hamilton, fearing mob rule -- he saw the role of the military as protecting the nation's republican style of government.

He took note of the dictatorial powers assumed by George Washington and Abraham Lincoln -- "arbitrary arrests, summary executions without trial, forced impressment of provisions, and other dangerous precedents" for Washington; and in Lincoln's case, the suspension of habeas corpus, arbitrary arrests, and the seizure of the railroads, along with "opening the treasury to irresponsible citizens" -- and concluded with a query. If that is what happens when good men without a genuine dictatorial impulse are president, what would happen if a true authoritarian took office and there was a war?

Upton wrote, "Let us not stultify ourselves by talking of the danger of an army, but rather reflect that the lack of one may at any time, in the space of two years, bring upon us even graver disasters than Long Island or Brandywine, or the two Bull Runs ... Our danger lies not in having a regular army but in the want of one."

In other words, Upton concluded a professional military, vowed to protect and defend the Constitution, as a safeguard against civilians, especially the president, grabbing dictatorial power.

Upton was one of several reformers, Fitzpatrick said, who saw the need for a more highly trained military and professional officer corps heading into the 20th century but in Upton's lifetime, most of Upton's reforms were thwarted by politics. For the North, another insurrection seemed impossible and there was no apparent external threat to U.S. sovereignty, so reform didn't seem like a pressing need. The South was distrustful of the Army in general following Reconstruction.

The lack of external threats prior to 1860 is also one reason Fitzpatrick thinks Upton's idea that the war could have lasted less than two years with better preparation is unrealistic.

While it's interesting to contemplate how history might be different if the Civil War had come to an end before 1863 -- no Jim Crow South, as one potential outcome -- it would have required the Union to have in place a large, well-trained and equipped Army by 1860 and Congress would never have approved the expenditure.

"The only reason to have a large, well-trained Army prior to 1860 was to repress the South and Congress would never have done it, so it's kind of a moot question," Fitzpatrick said. "You never could have ended the war in 1862 because you would never have gotten the Army you needed."

By 1881, Upton began suffering from debilitating headaches. He was transferred to the Presidio in San Francisco but managed to delay assuming the command for three months while he sought treatment in New York. A doctor diagnosed a sinus problem and provided an electric treatment, which brought no relief. Upton probably suffered from a brain tumor. He transferred to San Francisco but the headaches grew worse. On March 15, 1881, he wrote his last words. A two-sentence letter to the adjutant general to tender his resignation. He then apparently took his own life with a revolver.

He was proceeded in death by his wife, Emily, and they are buried together in Auburn.

At the time of his death, "Military Policy of the United States" was incomplete and unpublished. The manuscript passed to a friend and slowly it circulated among the Army's officers, gaining a reputation for its insightful look at military policy and strategy. In 1904, the War Department published the book minus three chapters.

One of the chapters dealt with Roman military history and when Fitzpatrick first came across it, he thought it rather odd. It was placed between two unrelated chapters, which was also odd.

Years later while continuing his research, Fitzpatrick recognized Upton probably wrote the chapter quickly in a period of inspiration and that it contained a lesson relevant the political situation of the time.

While Upton admired President Ulysses S. Grant as a general, he was appalled by the corruption in his administration.

The Roman Republic possesses an interest, civil as well as military. "Forewarned is forearmed." Free people like the Romans admire heroism and love to reward military achievement.

No monarch in Europe has to day [sic] the power of an American President. With the consent of the Senate, from the Chief Justice down, he has the gift of more than 90,000 civil offices, any one of which save the judiciary, he can vacate and fill at pleasure.

Ever since the acceptance of the pernicious maxim "To the victor belong the spoils," these offices, like so much gold have been distributed by the senators and representatives to the men who have been, or maybe, most loyal to themselves or the party.

With the people thus accustomed to executive corruption let us imagine, as under the Roman System, our President, in uniform, booted and spurred, galloping from the White House to the camp, his military retinue swelled by senators and representatives, fawning for favor and scrambling for spoils, how long it be asked would our liberties survive ...

To historian, from example of Rome, might not fix the exact duration of the Republic, but he could make at least one prophesy of speedy fullfllment: At the first [meeting] held at headquarters the means would be discussed of prolonging the term of the President, if not the more startling propositon to declare him President for life.

"Upton wasn't writing about Rome," Fitzpatrick said. "It was about Ulysses Grant. He was writing at a time when Grant, running for a third term in 1880, was being seriously discussed. He had come to a different opinion of Grant. He had seen all the scandals of Grant's administration, and while he admired Grant as a general, the scandals appalled him.

"He's not talking about an imaginary president climbing on a horse. He's talking about Grant. If Upton was really a militarist interested in a military government, that wouldn't have bothered him at all."

County historian to give talk on 'Becoming American: The Journey of Italians in Genesee County

Press release:

GO ART! is pleased to cosponsor this free presentation with the Oakfield Historical Society at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Oct. 3, at the Oakfield Community & Government Center. Michael Eula, Ph.D., Genesee County Historian, will speak on the history of Italians in Genesee County, a subject particularly interesting to the Oakfield community's history with the gypsum mine.

This talk is presented as part of GO ART!'s GO-C Series.

Eula gives the following introduction to his program:

"On November 2nd, 1905, an Italian immigrant, Gaitano Valente, while working as a miner in Oakfield for the United States Gypsum Company, was killed in an avalanche of rocks that were being excavated. Less than a year later, on September 13th, 1906, it was reported that “200 Italians from New York City” were being brought into Oakfield to work as strikebreakers for that same company. It was assumed that a riot would ensue – and as a result, there was a collection of guns to be used in the expected confrontation.

"These two incidents took place within a national context of mass Italian immigration punctuated by a perception of Italians as the 'other' – a characterization capable of producing the largest mass lynching to ever take place in American history – the infamous murder of eleven Italian immigrants in New Orleans in 1891. This event served as a catalyst for attacks on Italians throughout the nation. The obvious question, then, is how the Italian immigrants of the late nineteenth century – the 'other' as depicted routinely in the newspapers of the day – could become, only a few generations later, a respected and influential member of American society.

Focusing on this question in terms of Genesee County, we will follow the journey of the typical Italian immigrant in the late 1800s as he or she, in subsequent generations, evolved from the outsider on the margins of society into a member of the mainstream of Genesee County – and American – life.

Becoming American: The Journey of Italians in Genesee County, NY

By Michael Eula, Genesee County Historian

Tuesday, Oct. 3, 7 p.m.

Oakfield Community and Government Center

3219 Drake Street, Oakfield

Free admission. Co-sponsored by GO ART!'s GO-C Genesee-Orleans Culture Connects Series

Recovered home movie may show Amelia Earhart in Le Roy

ROC archive has obtained film shot by Harold W. Trott, who lived in the Livonia area, that may contain images of Amelia Earhart at the opening of the airport in Le Roy. It's definitely Earhart in the film, but whether it was shot at Le Roy isn't for certain.

Earhart is seen to speak briefly at a mic that is flagged WFBL. WFBL is a Syracuse radio station, but our local radio expert and broadcast history buff Dan Fischer, co-owner of WBTA, said it is possible, back in the era of fewer radio stations, that WFBL was in Le Roy for such a historic event.

The video also contains pictures of Charles Lindbergh at Sikorsky Airport Bridgeport, CT where he kept his “Spirit of St. Louis.”

Above, we've cued the video to start at the point were Earhart enters the film.

Make your reservations for historic Batavia Cemetery Association's Halloween Candlelight Ghost Walk

Press release:

Join us for some spooky fun on Saturday, Oct. 21st, when the Batavia Cemetery Association will host a candlelight guided ghost walk through the Historic Batavia Cemetery on Harvester Avenue in Batavia.

The tours will feature the famous and infamous movers and shakers who shaped and influenced the City of Batavia. The guided tour will bring guests to meet men and women of Batavia, who, for various reasons, held great power and exerted great influence in their day, were victims of tragic events, or both.

- Philemon Tracy, one of the few Confederate officers buried in the north;

- Ruth the unknown victim of a horrendous murder;

- Joseph Ellicott, a man of great power and great flaws; and

- William Morgan, the man who disappeared and was allegedly murdered before he could reveal the secrets of the Masons, are some of the ghosts who will tell their stories on the tour;

- Also visiting will be Rev. John H. Yates, poet, preacher, philanthropist, journalist and author of nationally known hymns;

- Civil War veteran General John H. Martindale, who was Military Governor of the District of Columbia in 1865;

- Dean and Mary Richmond, who greatly influenced civic life in Batavia in the 1800s, will meet with guests in their mausoleum on the last stop of the tour. Dean Richmond made a great fortune in Great Lakes shipping and was the second president of the New York Central Railroad. Mary Richmond vastly expanded her husband’s fortune after his death and sat on the boards of many businesses and civic organizations.

Tours begin at 7 p.m. and run every 15 minutes until 8:30 p.m. Admission is $10 and includes refreshments. Reservations are strongly recommended.

Some tickets may be available at the gate the evening of the event at Historic Batavia Cemetery, Harvester Avenue, Batavia. Proceeds benefit the upkeep and restoration of the cemetery.

For more information, or to make reservations, contact 343-3220.

Free HLOM presentation: 'Notes from Armageddon: Popular Propaganda, Postcards, and the Great War'

If you would like to RSVP, please contact the museum at 585-343-4727 or hollandlandoffice@gmail.com.

200 years of Stafford architecture is topic of talk & slide show by Cynthia Howk from Landmark Society of WNY

State Police history on display where it started, Batavia Downs

The first troopers to deploy in Western New York was in Batavia's Exhibition Park in September 1917, so Al Kurek thinks it's appropriate that displays celebrating the 100th anniversary of the New York State Police be held at the same location, now known as Batavia Downs.

"I started collecting historical memorabilia after I retired in 1990 and I've been doing it every day since then," said Kurek, who lives in East Pembroke. "This is our 100th anniversary and we have an active retired trooper organization in Batavia. We meet monthly and we decided to put this together as our last hurrah before we hit, oh, I don't know what you want to call it, but, you know, we're all in our 70s and pushing 80s."

There are vintage patrol cars, motor cycles and uniforms on display, as well as the accouterments of the trade, from billy clubs, pistols and handcuffs to crime scene cameras and forensic tools. There are also historical documents, including photos and info on every trooper to work in Troop A.

"We've got videos and memorabilia from the 66 and 77 snow storms, Kurek said. "We have a little bit on the Attica riot. We have the 3407 plane crash in Clarence, the 1980 Olympics, which everybody kind of likes. We've got a canine that will be here today and tomorrow -- nothing on Saturday -- but we have a German Shepherd here on Sunday."

The exhibition is open today, tomorrow and Sunday from noon to 6 p.m. each day.

Kurek also invited troopers and their families to bring in any items related to the history of Troop A.

Ending of History Heroes Summer Program celebration

The History Heroes program at the Holland Land Office Museum held its annual penny carnival on Thursday. Children participating in the summer program were able to set up their own carnival attractions and then play the games together.

Photos: HLOM history heros visit library and Batavia Showtime

Students participating in the Holland Land Office Museum's History Heroes program this summer are learning about World War I.

Recently they visited the Richmond Memorial Library and Batavia Showtime Theaters. There are 40 children enrolled in the eight-day program.

Info and photos provided by Anne Marie Starowitz.